Needless procedures: knee arthroscopy is one of the most common but least effective surgeries

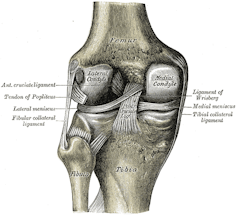

From time to time, we hear or read about medical procedures that can be ineffective and needlessly drive up the nation’s health-care costs. This occasional series will explore such procedures individually and explain why they could cause more harm than good in particular circumstances. More than 70,000 knee arthroscopies were performed in 2011 in Australia and, though rates of the surgical procedure are now falling, it still remains one of the most common surgical procedures. The word arthroscopy means to look inside a joint, in this case the knee. But newer imaging techniques, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, mean performing a knee arthroscopy simply to look inside the knee joint is rare. Knee arthroscopies are most commonly performed to treat osteoarthritis (wear and tear in the joint) or problems with the menisci (the two rubbery discs between the bone ends). An arthroscopy involves making a small incision in the skin and inserting a kind of camera on a stick. Another incision is made to insert other instruments to cut and remove tissue. In the case of osteoarthitis or meniscal problems, arthroscopy can be used to clear debris from the joint or to trim loose cartilage or torn parts of the menisci. The procedure can also be used to perform ligament reconstructions, help with treating fractures or infections in the knee, or simply to take a sample of tissue from the joint. The camera can see structures such as the cartilage that covers the end of the bones, the lining (synovium), the menisci and ligaments. Knee arthroscopy requires admission to hospital and an anaesthetic. It carries some risk of harm such as infection or further damage in the joint. Read more: Spinal fusion surgery for lower back pain: it's costly and there's little evidence it'll work It’s rarely effectiveMost knee arthroscopies are done in older people for degenerative conditions such as osteoarthritis. The prevalence of knee osteoarthritis, which can involve wear and tear of the menisci as well as the cartilage that lines the bone, increases with age. Most people aged 50 years and over have some osteoarthritis in the joint and roughly one-quarter will have some wear and tear in the menisci. Many people with osteoarthritis or a torn meniscus also have knee pain. This has led to the belief that the osteoarthritis changes or the meniscus tear cause the pain. But these changes are also common in those who have no pain at all. And menisci mostly don’t have nerves, so they can’t be felt unless there is a large tear, often resulting from a major injury. In fact, most people with a torn meniscus don’t have knee pain.

Many studies have now shown the outcomes from arthroscopic surgery for osteoarthritis and degenerative meniscal tears are no better than the outcomes from placebo (fake) surgery or other treatments (such as exercise therapy). A recent summary of these studies made “a strong recommendation against the use of arthroscopy in nearly all patients with degenerative knee disease” (osteoarthritis and degenerative tears of the menisci) and concluded “further research is unlikely to alter this recommendation”. Many surgeons believe the presence of mechanical symptoms – a concept that is not clearly defined but involves pain and abnormal feelings (such as catching, clicking and locking) when moving the joint – can be treated with arthroscopy. However, studies have also shown having arthroscopy does not provide better results than fake surgery for the treatment of mechanical symptoms. Sometimes, a meniscus can be so badly torn it folds over on itself, jamming the knee and restricting the ability to straighten the knee. This is a relatively uncommon type of meniscus tear and if the symptoms don’t improve on their own, the torn part of the meniscus can be removed arthroscopically. Why do surgeons still recommend it?Doctors tend to overestimate how good their treatments are and underestimate the harms that come from them. Surgeons are often faced with patients in pain and, other than surgery, have little else to offer except continued non-operative treatment, reassurance and time. Read more: Explainer: what is pain and what is happening when we feel it? Patients may want a quick fix or may have failed to improve with other treatments, but unfortunately the failure of other treatments doesn’t make knee arthroscopy any more successful.

Knee pain due to osteoarthritis often fluctuates in severity and patients tend to present for treatment when their pain is most severe. This means any treatment given at this time will appear more effective than it truly is. This is why comparative studies, particularly placebo studies, are important, as these show the true effects of treatments. Though some surgeons may believe they can predict which patients will do well from surgery, this belief has not been validated. Despite the desire for this procedure to work, arthroscopy for degenerative knee conditions puts patients at risk of harm, including death, for no important benefits. How can we stop it?Changing practice in response to evidence is often slow. The first high-quality trial to demonstrate knee arthroscopy was no better than placebo surgery was published in 2002, yet overuse of knee arthroscopy has persisted. Barring financial and regulatory controls, practice change in medicine is largely a social phenomenon. It requires leaders in the field and informed consumers to change practice. The rates of knee arthroscopy in Australia are starting to fall, particularly in New South Wales, where the rate of knee arthroscopies in people aged 50 and over has nearly halved since 2011. More action is needed. All surgeons, particularly in high-volume states such as Western Australia, South Australia and Victoria, need to take a good hard look at the evidence, question their practice, and take action to reduce this overuse. Read more: Needless medical procedures: when is a colonoscopy necessary? Ian Harris, Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, UNSW; Denise O'Connor, Senior Research Fellow, Monash University, and Rachelle Buchbinder, Professor of Clinical Epidemiology and Rheumatologist This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Comments are closed.

|

�

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

|

MENU

|

INJURY INFO

|

INJURY INFO

PHYSIO MOSMAN |

Copyright© 2024| Fit As A Physio | ABN 62855169241 | All rights reserved | Sitemap

RSS Feed

RSS Feed