|

I quite enjoy the concept of Micromorts & Microlives. Our average life expectancy can be divided into one-million, half-hour units. I enjoy the maths of risk. The things that add or subtract units of our lives.

For example:

Sitting Is Dangerous

There’s been some media over the last couple of years suggesting that “sitting is the new smoking”.

Research now tells us that the number of hours we sit each day is an independent predictor of our health, similar to other factors like age, smoking status, obesity, & exercise. It turns out that sitting for 10 hours a day is harmful for your health whether or not you exercise, how old you are, whether or not you smoke, & whether or not you’re fat or thin. Sitting is bad for you. The longer we sit, the less healthy we are. There are a couple of reasons… 1) Back Pain

Sitting is the primary cause of low back pain, which is a leading cause of disability in the general population (second only to depression), with nearly four million Australians suffering at any one time. Total treatment costs in Australia exceed $4 billion a year. Back pain is the most common musculoskeletal problem, accounting for one in four patients I see.

2) Inactivity

The longer we sit, the less physically active we are. Physical inactivity shortens our lives. It is the 4th leading cause of death. Physical inactivity is the second greatest contributor, behind tobacco smoking, to the cancer burden in Australia. Physical inactivity is estimated to be the main cause for approximately 25% of breast and colon cancers, 27% of diabetes, and approximately 30% of ischaemic heart disease.

From an evolutionary point of view we’ve had 100,000 generations of being hunter-gatherers, moving around, doing different things all day. We’ve only had 10 generations of industry, where we do the one thing all day, commonly including too much sitting. Our bodies just aren't used to sitting for long periods of time.

Sounds terrible? However, the solution is easy…

New research has found that getting up and moving around for two minutes every hour is associated with a 33% lower risk of dying prematurely. Breaking up the sitting time appears to be more beneficial to life expectancy than doing daily exercise. You can eliminate the harmful effects of sitting 10 hours a day by getting up for 2 mins every hour. Breaking up sitting time also is also good for back pain. I’ve spent years trying to get people to sit with better posture to prevent back pain. It’s super hard to maintain. It takes continuous deliberate effort, which is almost impossible. I’ve tried posture -aids, ergonomic chairs, lumbar supports, cushions, Swiss balls, taping. I’ve given up. You just can’t sit with perfect posture for long periods of time. I’ve now moved to trying to get people to get up and move for a couple of minutes every 20 minutes. You can get away with sitting with the worst posture imaginable if you don’t stay there too long. Overall it takes a lot less thought and effort for a much better result. I think the change to less sitting needs to be driven by employers over the next few years, similar to how smoking was fazed out of work places. I think we will see more stand-up desks, stand-up meetings, "walk-around" meetings, and possibly enforced limits on sitting time. So whether or not we do it for our backs or for a long life, we need to sit less & move more.

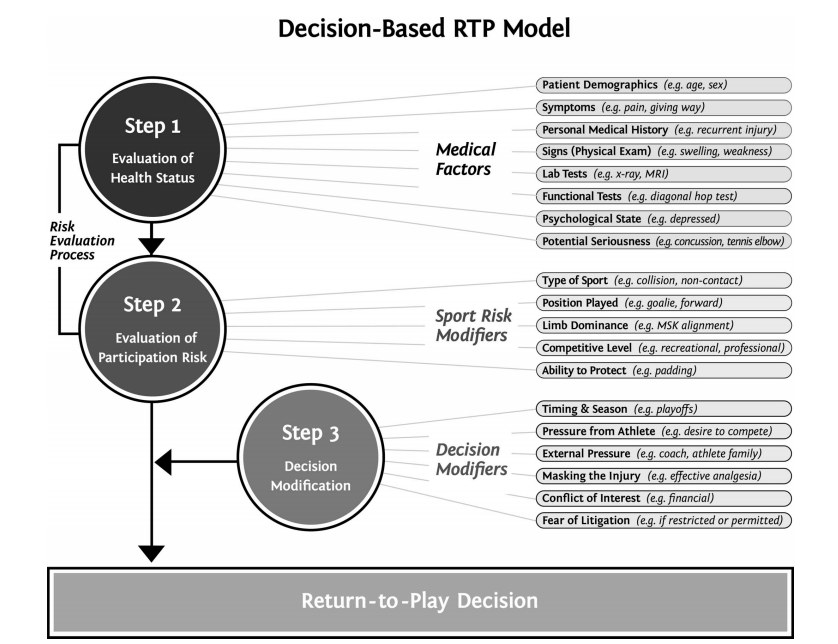

An essential part of diagnosing and treating sporting injuries is navigating a successful return to play. If you're a footballer, this means your first game back. If you're a runner it might mean returning to full training volumes.

It’s theoretically possible to return to play as soon as you’re able to stand up again, but obviously there’s a high chance of injury aggravation &/or recurrence. So, successful return to play isn’t just getting back on the field, but also doing our best to make sure:

For a lot of injuries we can agree on a rough timeframe of recovery based on our previous experience with similar injuries, and a known pattern of tissue healing. However, time alone is only a small component in determining successful return to play. This article (Creighton, 2010) outlines the extensive range of other considerations for negotiating a successful return to play: After assessing an injury I like to outline the milestones that are necessary to achieve a successful return to play. Physical factors may include:

This guides our treatment & gives us goals to work on with rehab, which may include:

Functional milestones need to be achieved sequentially. You need to pass one level to get to the next. Roughly, this might look like:

Progression through each of these functional stages may include:

By the time we return to the playing field we have confidence in the injury because we’ve done the work. Doing the rehab in a graded, progressive manner serves two purposes: 1). The exercise is conditioning, or “mechanotherapy”, to aid recovery. 2). It serves as a screening program, answering the question “am I OK to return to play?”. Doing the rehab gives us confidence that you’re OK to do “Z” because you’ve successfully completed “W”, “X”, & “Y”. Here is a graded, progressive running program I like you to progress through before returning to training. Here is a graded, progressive rehab programs for throwing & a similar rehab program for kicking. Injury Recurrence

Successful return to play isn’t just about getting back on the paddock.

We know the biggest risk factor for any injury is a previous history of the same injury. That means once you’ve had an injury, you’re at risk of re-injury. So successful return to play must include rehab aimed at preventing the same thing happening again. This might include specific stretching, strengthening, taping, bracing, proprioception, or skills. The job is only half done if you’re still at risk.

In Australia a lot of money is wasted on unnecessary medical tests. This means testing to confirm a diagnosis that is already obvious, and tests where the results won’t change the course of treatment.

A physio example is MRI for knee injuries. Clinical tests I do in the rooms give an accurate diagnosis. An MRI usually isn’t necessary & can be reserved for cases where the surgeon needs to decide on the type of operation to perform. If the knee is not a candidate for surgery, then an MRI isn’t going to change the course of rehabilitation.

Similarly with back and neck pain. Low back pain is the most commonly imaged musculoskeletal complaint. A healthcare professional may send you for an x-ray / CT / MRI to confirm a diagnosis or “rule out” something serious. Unfortunately the imaging rarely adds any additional information, and can actually make things worse.

Back pain is very common. It’s the most common musculoskeletal injury, and essentially everyone will have a sore back at some stage in their lives. Because it’s so common, we know a lot about it.

In nearly all cases, back pain is not serious and we can reach an accurate diagnosis without needing scans. We can rule out the scary, “worst case” diagnoses like fractures, infections, & tumours with some simple questions. We can test for potentially serious “structural” injuries with some simple tests in the rooms. However, back pain is rarely anything structural or serious, and imaging doesn’t add any useful information. Research tells us having a scan doesn’t change the treatment you need, or how fast you recover. We know nearly everyone recovers from back pain without needing a scan.

“Is imaging just a waste of time & money?”

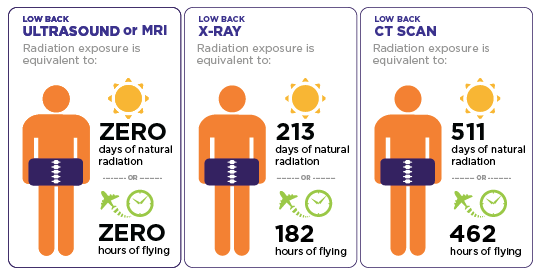

If you’ve got time and money, “what’s the harm?”. Well firstly, X-rays and CT scans expose you to radiation that can potentially cause cancers, so should only be performed when there is a clear benefit. Back X-rays deliver about 65 times more radiation than a chest X-ray. Back CTs expose you to 100 - 500 times the radiation of a chest X-ray. Would you volunteer for 500 X-rays if there wasn’t a clear benefit?

Possibly a bigger concern is, when we start scanning body parts, we see things.

MRIs can look nasty. There’s way too much detail. We see disc degeneration, disc bulges, degenerative joint disease, osteoarthritis, narrowing. But all of this is normal.

A study of adults without any back pain found that two-thirds of us have bulging discs or other spinal abnormalities on MRI scans. No pain. Bulging discs. So the bulging discs we see if we MRI your back pain are normal, and not something to worry about. Imaging for back pain shows us a lot of incidental findings that are unrelated to the pain. The changes we see on a scan don’t require any treatment. The radiologist writes a big long list of “problems”, however, they are just normal changes that were most likely there before you had your pain, and will most likely still be there once your pain has gone. Seeing these normal changes on the scan causes stress and anxiety, and potentially unnecessary follow-up tests and procedures, that add to the severity of the injury. Studies have found that back pain sufferers who had an MRI, compared to similar people with the same severity of injury:

Even though they had the same symptoms. Just because they’ve had a scan. A lot of reasons not to get a scan. Once we’ve seen something on a scan our expectations of recovery change, and that becomes self-fulfilling. If you think your back pain is serious it becomes more painful and takes longer to get better. “So choose wisely when your back hurts; remember that even brutal back pain is rarely a sign of serious pathology and that it’s really, really common.”

A systematic review and meta-analysis published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine has concluded PRP injections for osteoarthritis of the knee reduce pain and improve function when compared with placebo injections and hyaluronic acid injections.

However the results should be regarded with caution as almost all the analysed trials included a high risk of bias. Therefore further research is required. |

�

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

|

MENU

|

INJURY INFO

|

INJURY INFO

PHYSIO MOSMAN |

Copyright© 2024| Fit As A Physio | ABN 62855169241 | All rights reserved | Sitemap

RSS Feed

RSS Feed