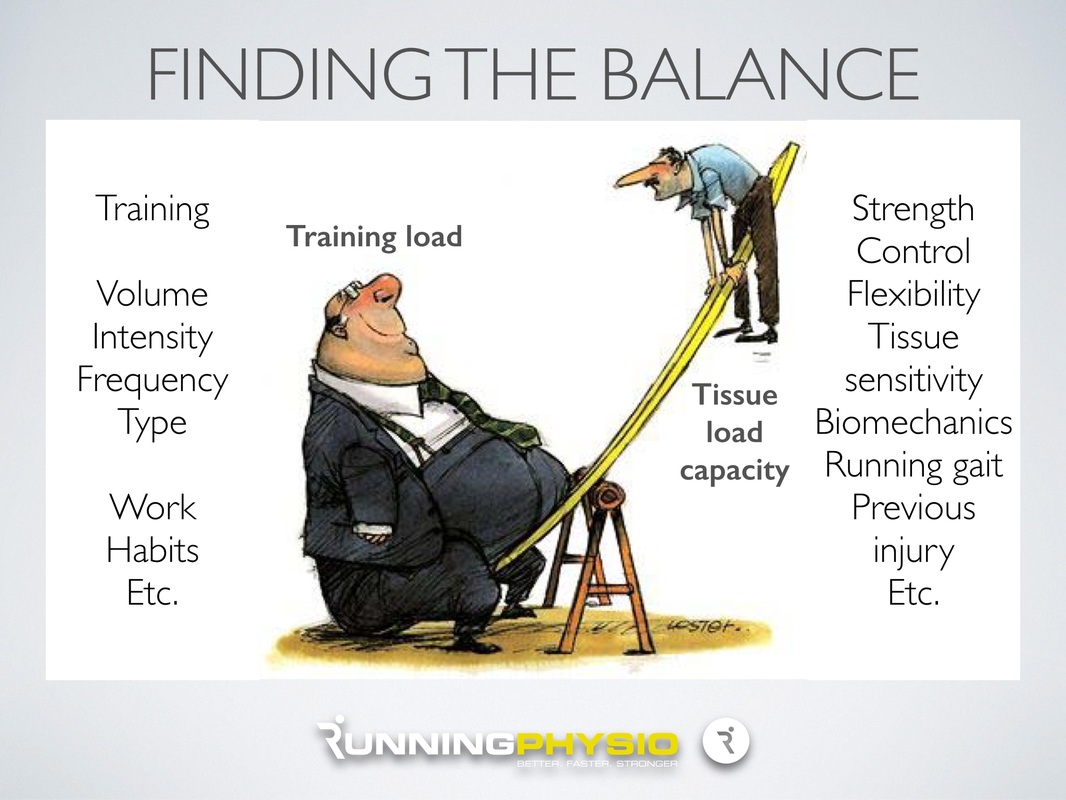

Load Management For Injury PreventionManaging training load is crucial in injury prevention and treatment. A graphic in Tom Goon’s recent blog visualises how training load outweighs all other factors. Historically we have advised that training loads shouldn’t increase by more than 10% a week. I’m not sure where this figure comes from. I’ve got no problem with it, it seems reasonable, and I’ve quoted it hundreds of times. There’s a recent BJSM podcast interview with Tim Gabbett on load management for injury prevention. Specifically Tim talks about this paper:

Spikes in acute workload are associated with increased injury risk in elite cricket fast bowlers

- Billy T Hulin, Tim J Gabbett, Peter Blanch, Paul Chapman, David Bailey, John W Orchard, 2013. It is research into fast bowlers but I think the principles apply just as well to any athlete. They measured the acute workload of the last 7 days (and call it “fatigue”) and compare that to the chronic workload of the previous 4 weeks (which they call “fitness”). Measuring Training Load

For runners, if the training is reasonably homogenous, we could most simply measure the workload as the total kms/week.

Or we could be more accurate and account for a mixed training program that may include a variety of hills / sprints / cross training etc, by giving each session a rate of perceived exertion (RPE) out of 10, and multiply that score by the number of training minutes:

Training load = session RPE x duration (minutes)

This is called a Foster’s Score, and provides a simple method for quantifying training loads from a variety of different training modalities.

The research subtracted the current 1-week average from the previous 4-week average and called this number the “training-stress balance”. A negative training-stress balance increases the risk of injury 4 times. So:

[Last 7 days’ session RPE x duration (minutes)] - ([Last 4 weeks’ session RPE x duration (minutes)] / 4) = TRAINING-STRESS BALANCE

Negative balance = 4 times risk of injury

Essentially this formula means you shouldn’t increase your training load by more than 25% a week.

For people that may be more vulnerable to injury I would change the 4-week average to a 6-week average, therefore, bringing the increase in load each week down from 25% to 16%. This more cautious group could include:

4/9/2015 10:51:20 pm

Great summary of the research and training stress balance. It's an important topic - but not well understood. Well done on getting the message out there. Tim

Fergus

5/9/2015 07:10:27 am

Thank you for your work Tim : ) It's great to have the research behind what we say. Comments are closed.

|

�

Archives

July 2024

Categories

All

|

|

|

MENU

|

INJURY INFO

|

INJURY INFO

PHYSIO MOSMAN |

Copyright© 2024| Fit As A Physio | ABN 62855169241 | All rights reserved | Sitemap

RSS Feed

RSS Feed