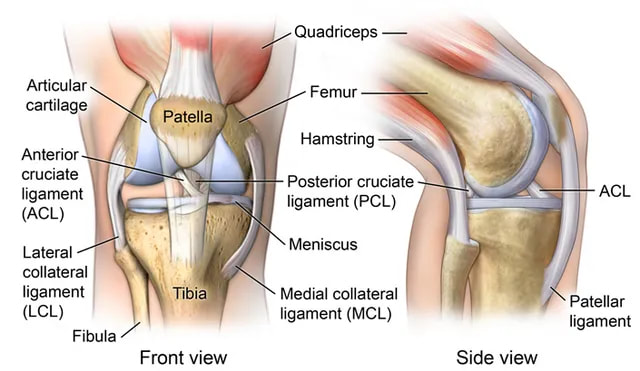

Ligaments are a bit like "ropes" that hold our joints together. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) crosses the middle of the knee ("cruciate" meaning "cross", from New Latin: "cruciātus") and plays a roll in stabilising the joint.

Unfortunately, the ACL can be injured playing sports that involve rapid change in direction, pivoting, side stepping, sudden stops, jumping and landing, or physical contact. Sports that have a higher risk of ACL injury include: skiing, soccer, AFL, rugby league, rugby union, touch football, Oz tag, netball, basketball, martial arts, mountain biking, motor cross, and gymnastics.

A full-thickness tear of the ACL is called a "rupture". The annual rate of ACL rupture in Australia is 0.05% per person per year. Professional athletes in basketball, soccer, and the other football codes report an annual incidence of 0.15%–3.7% (ref).

Female athletes tear their ACL at a higher rate than males, with a frequency of two to eight times higher, depending on the sport. The increased risk is attributed to differences in anatomy, muscle strength, and hormonal influences (ref).

Unfortunately, after treating the ACL rupture, there is a high rate of re-injury after returning to sport. For athletes younger than 25 who return to high-risk sport after reconstructive surgery, the incidence of recurrent ACL injury is 23% (ref).

Unfortunately, the ACL can be injured playing sports that involve rapid change in direction, pivoting, side stepping, sudden stops, jumping and landing, or physical contact. Sports that have a higher risk of ACL injury include: skiing, soccer, AFL, rugby league, rugby union, touch football, Oz tag, netball, basketball, martial arts, mountain biking, motor cross, and gymnastics.

A full-thickness tear of the ACL is called a "rupture". The annual rate of ACL rupture in Australia is 0.05% per person per year. Professional athletes in basketball, soccer, and the other football codes report an annual incidence of 0.15%–3.7% (ref).

Female athletes tear their ACL at a higher rate than males, with a frequency of two to eight times higher, depending on the sport. The increased risk is attributed to differences in anatomy, muscle strength, and hormonal influences (ref).

Unfortunately, after treating the ACL rupture, there is a high rate of re-injury after returning to sport. For athletes younger than 25 who return to high-risk sport after reconstructive surgery, the incidence of recurrent ACL injury is 23% (ref).

HAVE I RUPTURED MY ACL?

Symptoms vary depending on other structures in the knee that can potentially be damaged at the same time.

Symptoms may include (but not always):

If you think you have injured your ACL:

If an ACL injury is suspected, your doctor or physio will refer you for an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scan, which will provide detailed images of inside the knee. The MRI should take place within the first few days after injury. The MRI will allow a doctor to determine how badly you have injured the knee. You may also need an X-ray to rule out bone fracture(s).

Symptoms vary depending on other structures in the knee that can potentially be damaged at the same time.

Symptoms may include (but not always):

- Feeling the knee “giving way”

- Hearing a “snap" or “pop"

- Instant pain

- Rapid swelling

- Feeling of ongoing instability

- Pain with weight bearing

- Pain and stiffness with full flexion (bending) and extension (straightening).

If you think you have injured your ACL:

- First-aid instructions are here

- Range of Motion brace set to 30°-90°

- NWB on crutches

- Arrange for an "emergency" X-ray and MRI, specifically requesting a full sequence / double oblique sequence

with slices no greater than 3mm. (PRP Radiology at The Stadium Clinic reserve emergency MRI slots for ACL ruptures. PH: 8075 3400) - If in pain, use paracetamol. Avoid anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs, such as Nurofen).

If an ACL injury is suspected, your doctor or physio will refer you for an MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) scan, which will provide detailed images of inside the knee. The MRI should take place within the first few days after injury. The MRI will allow a doctor to determine how badly you have injured the knee. You may also need an X-ray to rule out bone fracture(s).

TREATMENT OPTIONS

After ACL rupture you can choose the treatment pathway most suited to your particular injury and circumstances. This includes surgical and non-surgical treatment options. Whatever pathway you choose, the aim is to restore functional stability to the knee and return safely to your preferred activities, and importantly, reduce the risk of sustaining another ACL injury.

Following acute injury to the ACL there have traditionally been two main treatment options, (1) surgery or (2) non-surgical rehabilitation. There is more recently a third option, the ACL Cross Bracing Protocol.

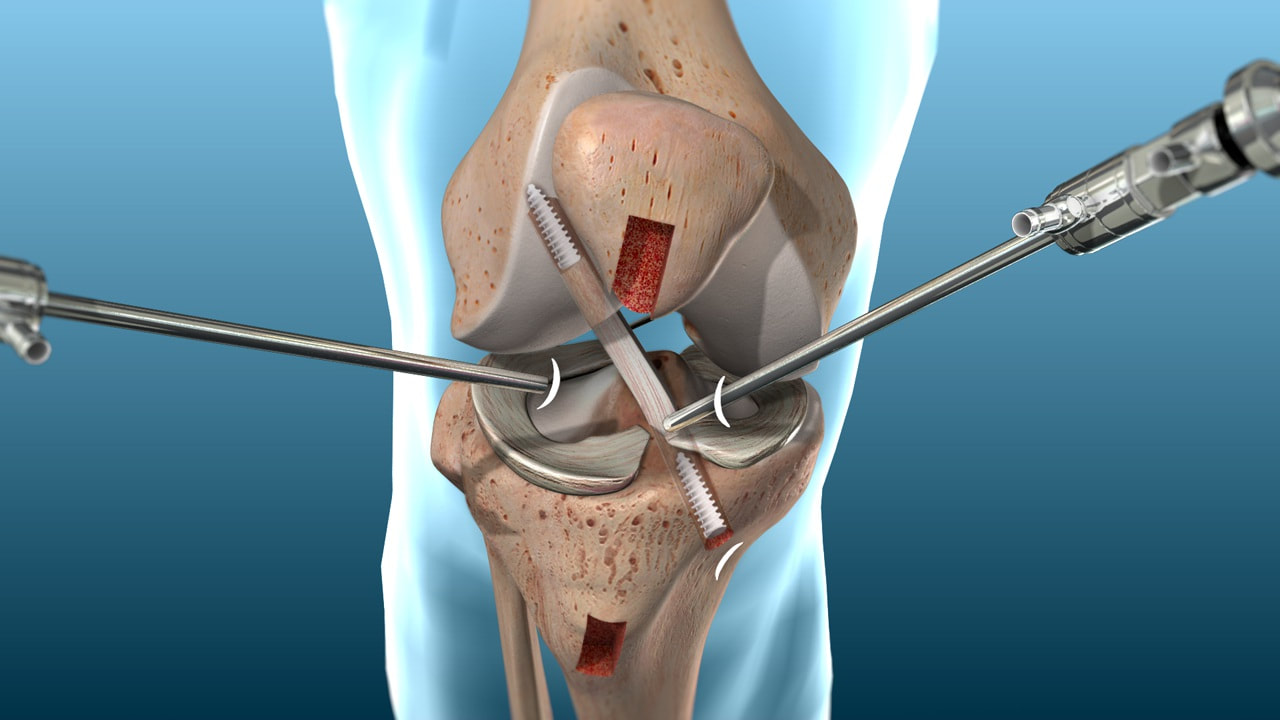

1. ACL RECONSTRUCTION SURGERY

In North America, Europe, and Australia, most ACL ruptures are treated surgically with ACL reconstruction (ACLR). ACL reconstruction, using graft material from the patient or a donor, has been practiced for decades, is well understood, and offers reliable results.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

After ACL rupture you can choose the treatment pathway most suited to your particular injury and circumstances. This includes surgical and non-surgical treatment options. Whatever pathway you choose, the aim is to restore functional stability to the knee and return safely to your preferred activities, and importantly, reduce the risk of sustaining another ACL injury.

Following acute injury to the ACL there have traditionally been two main treatment options, (1) surgery or (2) non-surgical rehabilitation. There is more recently a third option, the ACL Cross Bracing Protocol.

1. ACL RECONSTRUCTION SURGERY

In North America, Europe, and Australia, most ACL ruptures are treated surgically with ACL reconstruction (ACLR). ACL reconstruction, using graft material from the patient or a donor, has been practiced for decades, is well understood, and offers reliable results.

Advantages:

- A long history (over 40 years) of results giving a measure of outcome certainty.

- Other knee injuries, such as meniscal tears, can be addressed simultaneously.

Disadvantages:

- An invasive procedure.

- Expensive in the private health system, or 12-month waiting list in the public health system.

- 15%-30% re-rupture rate, depending on age / sport.

- Requires a long period of rehabilitation. Return to sport is not recommended before 12 months.

2. NON-SURGICAL REHABILITATION WITH OPTION FOR DELAYED SURGERY

An alternative treatment option to ACL reconstruction surgery is management with exercise-based rehabilitation. Non-surgical rehabilitation is widely practiced in northern Europe, where the public health authorities, after extensive research, deem this is the preferred management of acute ACL injury. Any patients who suffer ongoing knee instability and/or significant symptoms (pain, swelling, loss of function) are subsequently offered "delayed" ACL reconstructive surgery. This is also practiced by default in the UK where the NHS wait time for surgery is at least one year.

A 2014 prospective cohort study found there were essentially no differences in outcomes following non-surgical and surgical treatment of ACL injury. This included knee function, strength, time, sports participation, level of sport, and re-injury rate at 2-year followup (ref). A 2022 meta-analysis concluded that primary rehabilitation with optional delayed surgical reconstruction results in similar patient-reported outcomes for ACL rupture as early surgical reconstruction (ref).

Rehabilitation aims to strengthen the surrounding muscles to provide dynamic stability to the knee, to replace the static stability of the ACL.

Recent research is showing that, in some of these patients, the ACL actually heels without surgery. 2022 research suggests that about one-third of ruptured ACLs display evidence of healing on MRI when patients are managed with rehabilitation only, and that ACL healing is associated with favourable outcomes compared with early or delayed ACLR (ref). Approximately half (53%) of all participants randomised to rehabilitation who did not cross over to delayed ACL reconstruction (ACLR) had evidence of ACL healing on MRI at 2-year and 5-year follow-up.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

An alternative treatment option to ACL reconstruction surgery is management with exercise-based rehabilitation. Non-surgical rehabilitation is widely practiced in northern Europe, where the public health authorities, after extensive research, deem this is the preferred management of acute ACL injury. Any patients who suffer ongoing knee instability and/or significant symptoms (pain, swelling, loss of function) are subsequently offered "delayed" ACL reconstructive surgery. This is also practiced by default in the UK where the NHS wait time for surgery is at least one year.

A 2014 prospective cohort study found there were essentially no differences in outcomes following non-surgical and surgical treatment of ACL injury. This included knee function, strength, time, sports participation, level of sport, and re-injury rate at 2-year followup (ref). A 2022 meta-analysis concluded that primary rehabilitation with optional delayed surgical reconstruction results in similar patient-reported outcomes for ACL rupture as early surgical reconstruction (ref).

Rehabilitation aims to strengthen the surrounding muscles to provide dynamic stability to the knee, to replace the static stability of the ACL.

Recent research is showing that, in some of these patients, the ACL actually heels without surgery. 2022 research suggests that about one-third of ruptured ACLs display evidence of healing on MRI when patients are managed with rehabilitation only, and that ACL healing is associated with favourable outcomes compared with early or delayed ACLR (ref). Approximately half (53%) of all participants randomised to rehabilitation who did not cross over to delayed ACL reconstruction (ACLR) had evidence of ACL healing on MRI at 2-year and 5-year follow-up.

Advantages:

- Non-invasive

- A degree of efficacy found in clinical trials

- Less expensive

- Potential for ACL healing

- Return to sport between 3 and 6 months depending on damage to other structures in the knee

- Surgery is still an option for those who do not get a good result.

Disadvantages:

- Potentially an ACL deficient knee

- Concern regarding not doing "everything possible".

3. ACL CROSS BRACING PROTOCOL (CBP)

The Cross Bracing Protocol (CBP) is a specific form of non-surgical rehabilitation with the aim to facilitate and enhance the potential for the ACL to heal itself.

The bracing protocol puts the two ends of the ruptured ACL closer together, maximising the potential for the ligament to heal naturally while it is being protected. The bracing protocol is only suitable for about half of all acutely injured ACL patients. The other half of patients who are unlikely to benefit from the CBP can be offered surgery or may consider adopting “rehabilitation alone”.

Advantages:

Disadvantages:

More information on the ACL Cross Bracing Protocol is here.

The Cross Bracing Protocol (CBP) is a specific form of non-surgical rehabilitation with the aim to facilitate and enhance the potential for the ACL to heal itself.

The bracing protocol puts the two ends of the ruptured ACL closer together, maximising the potential for the ligament to heal naturally while it is being protected. The bracing protocol is only suitable for about half of all acutely injured ACL patients. The other half of patients who are unlikely to benefit from the CBP can be offered surgery or may consider adopting “rehabilitation alone”.

Advantages:

- An anatomically healed ACL is hypothesised to be as strong as the patient’s original ACL tissue.

- Non-invasive

- A degree of efficacy found in clinical trials

- Less expensive

- Surgery still an option for those who do not get a good result.

Disadvantages:

- The need to wear a knee brace for twelve weeks. This is both challenging and inconvenient. The analogy that a ruptured ACL is equivalent to a fractured tibia that will heal without surgery, but there is a need for immobilisation (a plaster cast for the fractured tibia) and crutches.

- Requires a long period of rehabilitation

- Return to sport is not recommended before 12 months.

More information on the ACL Cross Bracing Protocol is here.

A good website that provides more information about surgical and non-surgical options to help you make a decision, is: www.aclinjurytreatment.com