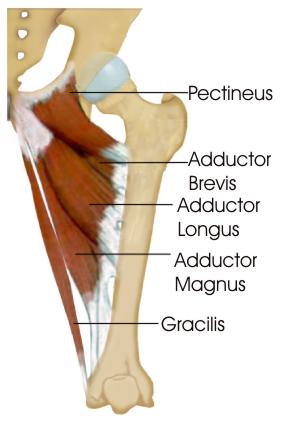

A recently published article by Haroy et al, in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, described a simple exercise routine that decreased the number of groin injuries in male footballers by 41%. Groin injuries are very common in football. Research shows that weaker groin muscles are associated with an increased risk of groin muscle injury. So strengthening groin muscles can potentially prevent injury. The paper studied the Copenhagen Adduction exercise, which has previously been shown to strongly recruit adductor longus. Haroy et al, offered the Copenhagen at three levels of resistance, based on the players’ pain. Players started with Level 3. If the exercise gave them more than 3/10 pain, they were instructed to do the exercise level below instead: 3 > 2 > 1.

The training protocol is shown in the following table: Being only one, quick exercise, compliance was high. They found performing the Copenhagens decreased the risk of groin injury by 41%.

The full article is HERE. Copenhagens are definitely worth adding to your training. The concept is similar to strengthening hamstrings with the Nordic Hamstring Curl which has been shown to prevent 70%-85% of hamstring strain injuries.

HEEL PAIN IN CHILDREN

Sever’s is most common in 9 - 12 year olds. It’s sore to squeeze the bone at the base of the Achilles where it attaches onto the heel. It’s not something that can be seen - it never seems to look red or swollen. It’s worse after sprinting, jumping, and hopping. It settles with rest. It is an overuse injury so it’s common in pre-season, or anytime training loads increase too quickly. My kids get it when they do extra sessions in running spikes or footy boots, without the normal heel support of their running shoes. It’s an overuse injury from excessive loads.

OVERUSE INJURY

When we talk about excessive loads it can be “external” load such as:

I think the running pace is the more powerful multiplier in this list. Extra sprint sessions will do it. My kids got sore once when we did a boot-camp session with a novel plyometric exercise - split jumps. There are also “internal” variables that determine our ability to cope with the training load:

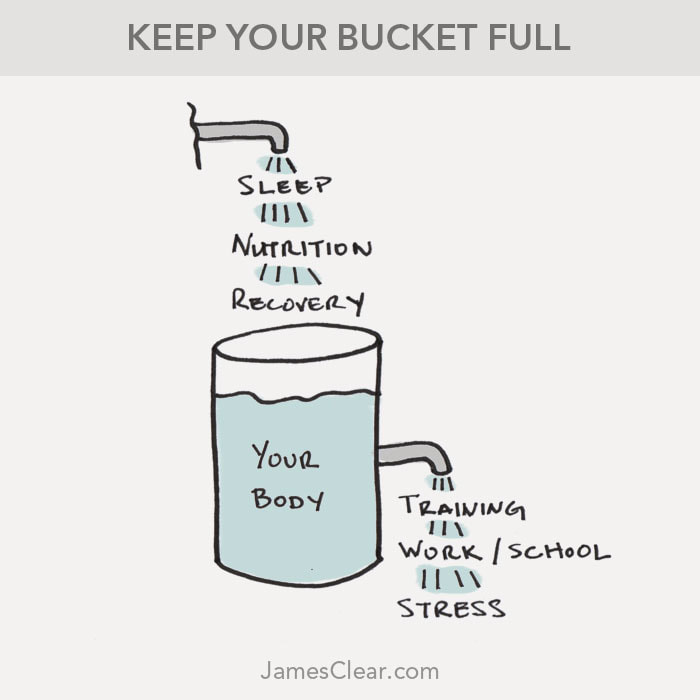

My kids definitely are more prone to Sever’s if they’ve had a couple of late nights that week. And, if they’re having a growth spurt, their bodies are busy spending resources on growing rather than recovering from the stress of a training session. NATURAL RECOVERY

Text books say that Sever’s disease is self-limiting because the growth plate eventually fuses by the age of 15 or 16. But I don’t think there’s anyone who would be happy to just let it run its course until then. It is usually sore enough to stop you participating in sport, so it needs treatment.

WHAT DO WE DO?

I used to put kids with heel pain in orthotics, until I read this research which confirms that a simple heel wedge is more effective than orthotics for Sever’s disease.

I get them to do an isometric Achilles strengthening program which also helps with pain control. But ultimately recovery comes down to load management. Load management means reducing the excessive loads. So this could be:

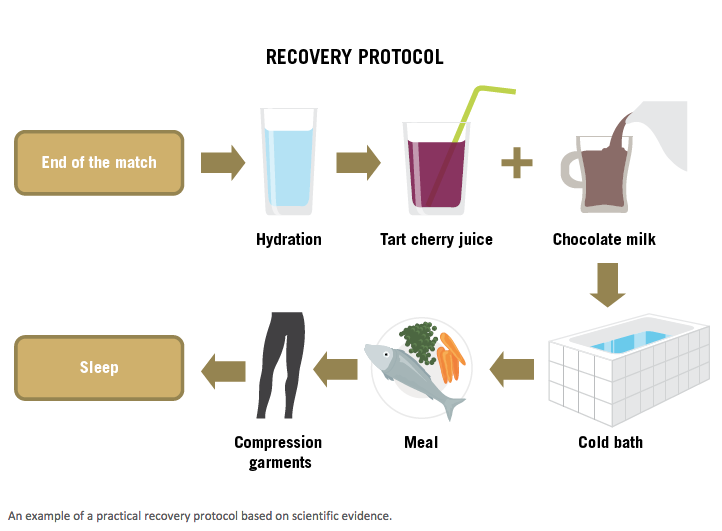

And aid recovery with:

With these type of overuse injuries, I interpret "soreness" as essentially the same thing as "tiredness". If they've been training more, sleeping less, or growing more, we would expect some "tiredness". If they were tired what would be the treatment?... Sleep more and train a bit less.

Summary of:

FOOTBALL RECOVERY STRATEGIES (Grégory Dupont, Mathieu Nédélec, Alan McCall, Serge Berthoin and Nicola A. Maffiuletti, 2015) Does Fatigue Cause injury?

|

| Often when I’m talking to my patient about their injury and why it has happened, they guiltily report that they don’t stretch enough. We’ve all grown up being told how important is it to stretch:

|

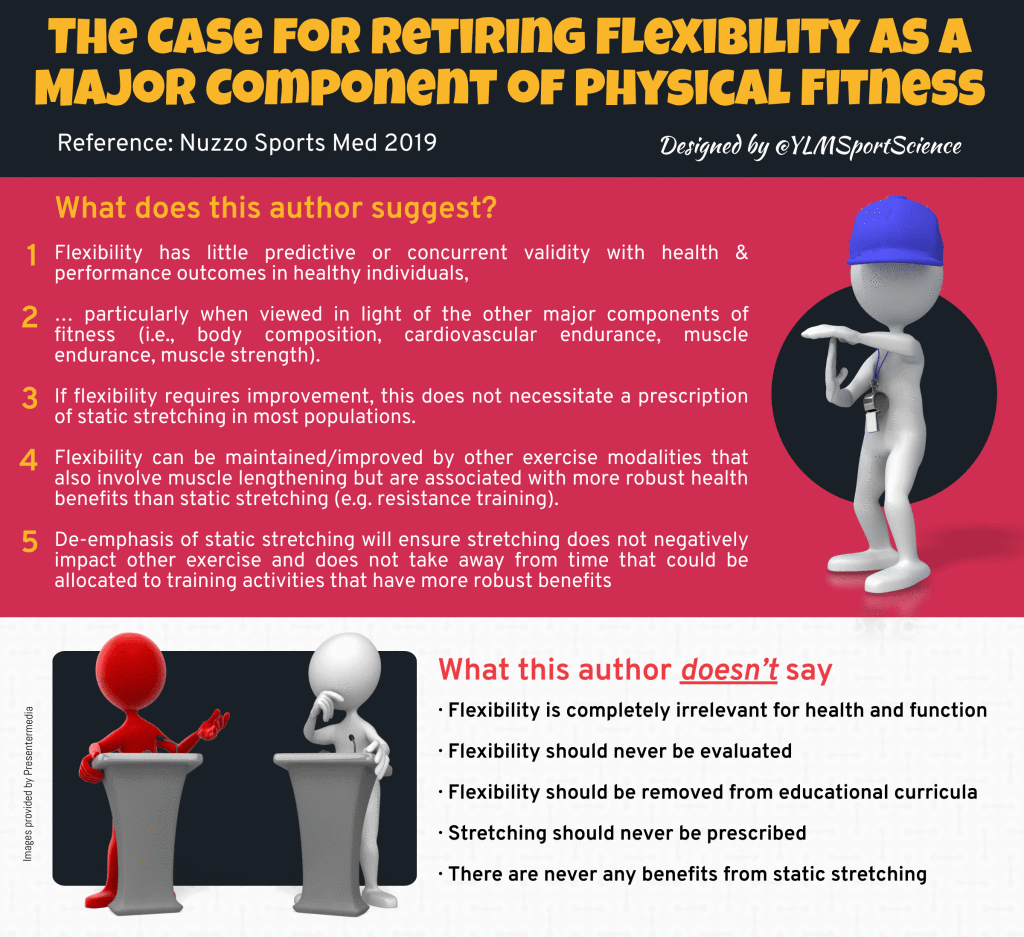

Interestingly, health professionals have changed our tune about the importance of stretching. Research over the last 15 years has suggested static stretching is not as beneficial as was once thought. I’ve been having conversations about the reasons to stretch (or not) for at least the last 15 years, but the current science on stretching just isn’t catching on.

So, what do we know?…

DOES STRETCHING PREVENT INJURIES?

Therefore, in practical terms the average athlete would need to stretch for 23 years to prevent one injury. Definitely not worth it.

DOES STRETCHING HELP MUSCLE SORENESS?

DOES STRETCHING INCREASE RANGE OF MOVEMENT?

DOES STRETCHING HELP PERFORMANCE?

A substantial body of research has shown that sustained static stretching acutely decreases muscle strength and power (ref). Stretching before an endurance event lowers endurance performance and increases the energy cost of running (ref). Cycling efficiency and time to exhaustion are reduced after static stretching (ref).

Pretty much any measure of performance is made worse by stretching. Static stretching impairs:

- strength

- maximal voluntary contraction

- isometric force

- isokinetic torque

- one repetition maximum lifts

- power

- vertical jump

- sprint times

- running economy

- agility

- balance

A comprehensive review (ref) from 2011 concludes:

WHAT ABOUT DYNAMIC STRETCHING?

SO WHY STRETCH?

SO SHOULD WE STOP STRETCHING?

- Will introducing independent doctors at games help the AFL tackle its concussion problem? -

- The unstoppable rise of the carbon-fibre super shoe -

- Muscle building and resistance training often get ignored, but they're likely to help us age better -

- Evidence doesn't support spinal cord stimulators for chronic back pain -

- Surgery won't fix my chronic back pain, so what will? -

- Can a good night's sleep protect collision sport athletes against concussion? -

- Beetroot isn't vegetable Viagra. But here's what else it can do -

- New research suggests intermittent fasting increases the risk of dying from heart disease -

- AFL considers independent doctors at games to help assess head knocks -

- The role of the physiotherapist in concussion in sport -

- Six tips for sticking to your fitness goals -

- How Cold Weather Saps Your Endurance -

- Esports, pickleball and obstacle course racing are surging in popularity - what are their health benefits and challenges? -

- Football codes' lack of response to AIS concussion guidelines leaves players in limbo for 2024 season -

- Insufficient Evidence for Load as the Primary Cause of Nonspecific Chronic Low Back Pain -

- Does playing football really increase the risk of knee osteoarthritis? -

- AFL changes concussion guidelines for community football but elite level protocols stay the same -

- Gabrielle is hesitant to return to sport after an ACL injury -

Some pain or discomfort during exercise is OK and safe. It is a good sign if your pain warms up as you exercise and doesn’t feel worse the next day.

KEEP MOVING

Resting too much can be more aggravating than staying active. Reduce your training volume enough to settle symptoms and ensure you don’t feel worse the next day.

PLAN AHEAD

Avoid consecutive days of impact exercise (like running and jumping) if you are sore.

/ Sunday / - / Tuesday / - / Thursday / - / Saturday /

MONITOR MORNING STIFFNESS & SYMPTOMS

Low and stable symptoms are OK. A spike in stiffness, tightness, or pain, means you’ve probably overdone it the day before. You don’t need complete rest. Continue resistance training, do less impact training.

BE PATIENT

There’s no quick fix.

GENERAL HEALTH

We also need to consider general health variables that contribute to recovery:

- Nutrition

- Hydration

- Stress

- Sleep

J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2024;54(1):95. doi:10.2519/jospt.2023.9001

- Smart mouthguard the new weapon in rugby concussion -

- Athletes struggling with contraceptives and menstrual health as periods remain taboo in sport -

- I want to eat healthily. So why do I crave sugar, salt and carbs? -

- "Naked carbs" and "net carbs" - what are they and should you count them? -

- High Intensity Exercise Can Reverse Neurodegeneration in Parkinson's Disease -

- Inside the brain of a suspected CTE patient -

- Gradual acceptance of concussion risk prompts new reality for Australian sport -

BPPV is caused by a problem with the inner ear, where a small calcium deposit forms and moves with gravity around the different angled canals of the inner ear. BPPV is “positional” as it is triggered by specific head movements, for example, turning your head to the left with rolling over in bed. Symptoms of vertigo are room spinning, disturbed balance, and nausea.

BPPV typically resolves within a few weeks, but can be recurring.

Your GP can give you anti-nausea medication, and Physiotherapists treat BPPV with a sequence of movements and positions, called the Epley Manoeuvre, that uses gravity to re-position the calcium crystals.

A video of the Dix Hallpike test for BPPV is HERE.

Information on the Epley Manoeuvre is HERE.

A video of the Epley Manoeuvre is HERE.

Do you have vertigo? Book a physiotherapy appointment in Mosman to perform the Epley Manoeuvre HERE.

- Can kimchi really help you lose weight? -

- How exercise can treat and prevent common mental health issues -

- Can Strength Training Protect You From Running Injuries? -

- Running or Yoga can help beat depression -

- Many of the supposed benefits of sauna and ice baths are not backed by solid evidence -

- Is it broken? A strain or sprain? How to spot a serious injury -

- How long does back pain last? And how can learning about pain increase the chance of recovery? -

- Concussion in sport: why making players sit out for 21 days afterwards is a good idea -

- How much weight do you actually need to lose? It might be a lot less than you think -

- Fempro Armour looks to minimise sporting injuries among women -

- NRL concussion revolution: Contact training limit on cards -

- How long does low back pain last and what treatments can help? -

- Why the biggest threat to the Matildas' knees is sitting on a plane -

- How women respond to strength training -

Archives

July 2024

June 2024

May 2024

April 2024

March 2024

February 2024

January 2024

December 2023

November 2023

October 2023

September 2023

August 2023

July 2023

June 2023

May 2023

April 2023

March 2023

February 2023

January 2023

December 2022

November 2022

October 2022

September 2022

August 2022

July 2022

June 2022

May 2022

April 2022

March 2022

February 2022

January 2022

December 2021

November 2021

October 2021

September 2021

August 2021

July 2021

June 2021

May 2021

April 2021

March 2021

February 2021

January 2021

December 2020

November 2020

October 2020

September 2020

August 2020

July 2020

June 2020

May 2020

April 2020

March 2020

February 2020

December 2019

November 2019

October 2019

September 2019

August 2019

July 2019

June 2019

May 2019

April 2019

March 2019

January 2019

December 2018

November 2018

October 2018

September 2018

August 2018

July 2018

June 2018

May 2018

April 2018

March 2018

February 2018

January 2018

December 2017

November 2017

October 2017

September 2017

August 2017

July 2017

June 2017

May 2017

April 2017

March 2017

February 2017

January 2017

December 2016

November 2016

May 2016

November 2015

October 2015

September 2015

August 2015

July 2015

June 2015

May 2015

Categories

All

Achilles

ACL

Active Transport

Acupuncture

Ageing

AHPRA

Alcohol

Ankle

Ankylosing Spondylitis

Apps

Arthritis

Arthroscopy

Babies

Backpacks

Back Pain

Blood Pressure

BMI

Body Image

Bunions

Bursitis

Cancer

Chiro

Chiropractic

Cholesterol

Chronic Pain

Concussion

Copenhagen

Costochondritis

Cramp

Crossfit

Cycling

Dance

Dementia

Depression

De Quervains

Diet

Dieting

Elbow

Exercise

Falls

Fat

Feet

Fibromyalgia

Fibula

Finger

Fitness Test

Food

Foot

Fracture

Fractures

Glucosamine

Golfers Elbow

Groin

GTN

Hamstring

Health

Heart-disease

Heart-failure

Heat

HIIT Training

Hip-fracture

Hydration

Hyperalgesia

Ibuprofen

Injections

Injury

Injury Prevention

Isometric Exercise

Knee

Knee Arthroscopy

Knee Replacement

Knees

LARs Ligament Reconstruction

Lisfranc

Load

Low Back Pain

Massage

Meditation

Meniscus

Minimalist Shoes

MRI

MS

Multiple Sclerosis

Netball

Nutrition

OA

Obesity

Orthotics

Osgood-Schlatter

Osteoarthritis

Osteopath

Osteoperosis

Pain

Parkinsons

Patella

Peroneal-tendonitis

Physical-activity

Physio

Physio Mosman

Pigeon-toed

Pilates

Piriformis

Pokemon

Posture

Prehab

Prolotherapy

Pronation

PRP

Radiology

Recovery

Rehab

Rheumatoid

Rheumatoid-arthritis

Rotator Cuff

RTP

Rugby

Running

Running Shoes

Scan

Severs

Shin-pain

Shoes

Shoulder

Shoulder Dislocation

Sitting

Sleep

Soccer

Spinal-fusion

Spondyloarthritis

Spondylolisthesis

Sports Injury

Sports Physio

Standing

Standing-desk

Statins

Stem-cells

Stress Fracture

Stretching

Sugar

Supplements

Surgery

Sweat

Tendinopathy

Tendinosis

Tendonitis

Tmj

Treatment

Vertigo

Walking

Warm-Up

Weight Loss

Wheezing

Whiplash

Wrist

Yoga

RSS Feed

RSS Feed